When you delve into fiction, whether it's a gripping novel, a chilling film, or even an anime saga, you're often engaging with far more than just the surface narrative. You're swimming in a sea of implied meanings, emotional undertones, and sometimes, unsettling truths. Mastering Symbolism & Darker Tones Analysis is the key to unlocking these hidden depths, revealing how authors craft mood, foreshadow events, and infuse their stories with profound meaning, often using shadows as much as light.

This isn't about over-analyzing every detail until the joy is sucked out of reading. Instead, it's about sharpening your perceptive skills, allowing you to appreciate the artistry behind stories that truly resonate. It's about understanding why a simple object can send shivers down your spine, or why a character's seemingly innocent choice carries a heavy, unspoken weight.

At a Glance: Deciphering the Hidden Language of Fiction

- Symbolism isn't just decoration: It's a powerful literary tool where concrete elements (objects, settings, names) represent abstract ideas, deepening the narrative.

- Context is King: Symbols aren't universal. What signifies good luck in one culture might mean danger in another. Always consider the socio-cultural backdrop.

- Spot the Clues: Look for conventional meanings, elements that seem "plot irrelevant," repetition, or unusually detailed descriptions to identify potential symbols.

- Allegory is a System: Beyond individual symbols, allegory creates an entire narrative where characters, events, and settings systematically represent abstract concepts.

- Unpack the Meaning: Once identified, connect symbols to the story's overarching themes. Ask what ideas they evoke and how they cohere with the broader narrative.

- Color Tells a Story: Authors deliberately use color to convey mood, character traits, and thematic ideas, with darker hues often signaling mystery, danger, or foreboding.

- Beware the Subversion: Skilled writers can twist conventional symbols, using familiar imagery in unexpected ways to create irony or inject darker undertones.

Beyond the Surface: What Exactly is Literary Symbolism?

At its heart, symbolism is the literary magic trick of making one thing stand for another. It's when an object, a plot occurrence, an aspect of the setting, or even a character's name isn't just itself, but also represents an abstract idea. Think of it like this: a rotting melon in a story isn't just a piece of spoiled fruit; it could be a symbol for wasted promise, lost potential, or the decay of a relationship. A sudden downturn in the weather? It might not just be rain; it could be mirroring the storm brewing in a character's life, signaling negative circumstances to come.

This is distinct from a metaphor. A metaphor is a verbal comparison—"Her anger was a storm." A symbol, however, is something that literally exists within the narrative world, yet it carries a deeper, non-literal meaning that ripples beneath the surface of the story. It adds texture, emotional weight, and intellectual depth without needing explicit explanation.

The power of symbolism lies in its ability to refine our human capacity to perceive and evoke abstract concepts through concrete details. It's how a writer can connect the steady drip of sand in an hourglass to the crushing finiteness of life, allowing you to feel the concept rather than just read about it.

Decoding the Cultural Code: When a Symbol Isn't Universal

While some symbols feel universal, like a heart for love, the truth is that meaning is deeply rooted in culture. Every society possesses a vast reservoir of "stock symbols" – objects or actions with conventionally understood meanings that are passed down through generations.

Take a red rose, for instance. In many Western cultures, it's an undeniable symbol of passionate desire or romantic love. A yellow rose, by contrast, typically signifies friendship. An owl, often associated with the Greek goddess Athena, commonly represents wisdom and knowledge. And the olive branch? Thanks to its biblical origins in the story of Noah, it's widely understood as a symbol of peace. When you encounter these elements in fiction, it’s worth considering if the author is consciously drawing upon these established meanings.

However, these meanings are far from universal. The very color red, which screams "danger" or "passion" in Western contexts, is often seen as a symbol of good luck and prosperity in Chinese culture. An oasis, for someone living in a desert region, carries profound symbolic overtones of protection, life, and survival – meanings that would likely be absent or greatly diminished for someone from a North Atlantic tradition, where water is plentiful.

This cultural specificity is crucial for Symbolism & Darker Tones Analysis. To truly understand a text, you need to engage with its socio-cultural context. Ignoring this can lead to misinterpretations or, worse, missing the author's intended critique or nuanced message entirely. A story written in one cultural tradition might use symbols that resonate deeply with its intended audience, but require a bit more groundwork for readers from different backgrounds.

Spotting the Clues: How to Recognize a Symbol in the Wild

It's tempting to see symbols everywhere once you start looking, but as the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud famously quipped, "sometimes a snake is just a snake." Not everything in a narrative is symbolic, and over-analyzing can detract from the sheer enjoyment of the story. So, how do you differentiate a plain old snake from one laden with deeper meaning?

Here are key indicators to help you recognize potential symbols without turning every rock into a hidden message:

- Conventional Symbolism: Does the object already have a strong, widely recognized conventional meaning? If a fox appears, is it simply an animal, or is it embodying cunning and trickery, as is often the case in folklore? If a dove flies through the scene, is it just a bird, or is it bringing a sense of peace or innocence? Authors often lean on these established meanings, or cleverly subvert them to create irony or deeper impact.

- Plot Irrelevance (or Apparent Irrelevance): If something appears in the narrative, is described in some detail, but doesn't seem to serve a clear, direct role in advancing the plot, it might be symbolic. An ancient olive tree standing majestically in a town square, meticulously described over several paragraphs, might not contribute to the character's journey, but it could symbolize enduring wisdom, history, or resilience. If you can remove it without changing the immediate events of the plot, but something feels lost thematically, it's likely a symbol.

- Repetition: When images, objects, or phrases recur throughout a story, pay close attention. Repeated elements often suggest a symbolic function. If bulldozers keep appearing in various scenes, perhaps destroying old structures or disrupting nature, they might symbolize industrialization, progress at a cost, or the destruction of tradition. This repetition forces the reader to notice and question its significance.

- Lingering Description: Does the narrator spend an unusual amount of time describing a particular object or setting? A half-page dedicated to an abstract painting hanging on a wall, detailing its colors, shapes, and the feelings it evokes, is a strong signal that this painting isn't just set dressing. It's probably imbued with significant symbolic meaning, perhaps reflecting a character's inner turmoil, the fractured nature of their reality, or a hidden truth about the world of the story.

By keeping these indicators in mind, you can approach texts with a detective's eye, sifting through the literal to unearth the symbolic treasures within.

When Symbols Tell a Grand Story: Understanding Allegory

While individual symbols add depth, sometimes an entire narrative is constructed as a complex web of interconnected symbols. This is where allegory comes in. An allegory is a type of narrative where characters, plot events, and even settings all simultaneously represent abstract ideas or historical figures. It's like a story being told on two levels: a literal one and a symbolic one that runs consistently throughout.

Think of the medieval "Everyman" plays, for example. You have a character named "Everyman" who literally symbolizes any European Christian. He interacts with characters like "Fellowship," "Good Deeds," and "Knowledge," who aren't just names but embodiments of these moral forces. The entire play becomes an allegorical journey about morality, sin, and salvation.

Allegories can be quite direct, with clear equivalences, or they can be much more subtle and nuanced. George Orwell's Animal Farm is a masterclass in subtle allegory. On the surface, it's a fable about farm animals rebelling against their human owner. But every animal and farmer character represents a figure from the Russian Revolution or European aristocracies (e.g., the pigs Napoleon and Snowball symbolize Stalin and Trotsky; Farmer Jones symbolizes the Czar). The farm itself represents Russia, and the events mirror the rise and fall of Soviet communism. It's a powerful political allegory that works both as a simple story and as a biting critique.

You can also view allegory as a reading strategy. Even if an author didn't explicitly intend an allegory, some texts lend themselves to an allegorical interpretation, allowing readers to find consistent, overarching symbolic meanings across multiple narrative elements. It's a testament to the enduring power of stories to resonate on multiple levels.

Unpacking the Layers: A Step-by-Step Guide to Symbol Analysis

Once you've identified a potential symbol, the real work (and fun) of Symbolism & Darker Tones Analysis begins: connecting it to the work's larger themes and meaning. This isn't about finding one right answer, but exploring the rich tapestry of possibilities.

Here’s a practical approach to unpacking a symbol's significance:

- Identify the Concrete: What is the specific object, image, or event you're focusing on? Describe it literally. Is it a black bird? A wilting flower? A locked gate?

- Brainstorm Conventional Associations: What ideas, feelings, or concepts does this concrete item conventionally evoke?

- Black bird: Mystery, death, omen, freedom, intelligence.

- Wilting flower: Fragility, decay, lost beauty, fleeting life, sadness.

- Locked gate: Obstacle, protection, exclusion, secrecy, security.

- Consider its Context in the Narrative:

- Where and when does it appear? Is it at a pivotal moment? During a character's transformation? In a specific setting (e.g., a dark forest vs. a sunlit field)?

- Who interacts with it, or who observes it? Do different characters have different reactions or interpretations?

- What is its physical description? Is it old or new, beautiful or ugly, pristine or decaying? These details matter. For instance, a half-page description of an abstract painting is a strong signal of its symbolic weight.

- Look for Narrator or Character Commentary: Does the narrator offer any direct or indirect thoughts about the object? Do characters discuss it, or project their feelings onto it? Their perspectives can be guiding lights – or misleading ones, adding to the story's complexity.

- Connect to Overarching Themes: How do the ideas evoked by the symbol relate to the broader themes of the story?

- If the story is about loss and grief, a wilting flower powerfully underscores the fragility of life.

- If the story is about societal repression, a locked gate highlights the theme of freedom denied.

- A symbol gains true power when it coheres with other meanings developed in the narrative. For example, a black shirt might not symbolize evil if the character wearing it is otherwise morally upright and compassionate; it might symbolize mourning, sophistication, or rebellion.

- Explore Ambiguity and Subversion: Does the symbol's meaning shift over the course of the narrative? Does the author use a conventional symbol in an unconventional way, perhaps to create irony or inject a darker, unexpected twist? The most compelling symbols often resist a single, neat interpretation.

By systematically asking these questions, you move beyond simply identifying a symbol to genuinely analyzing its contribution to the story's mood, meaning, and emotional impact.

The Palette of Mood: Exploring Color Symbolism (and its Darker Side)

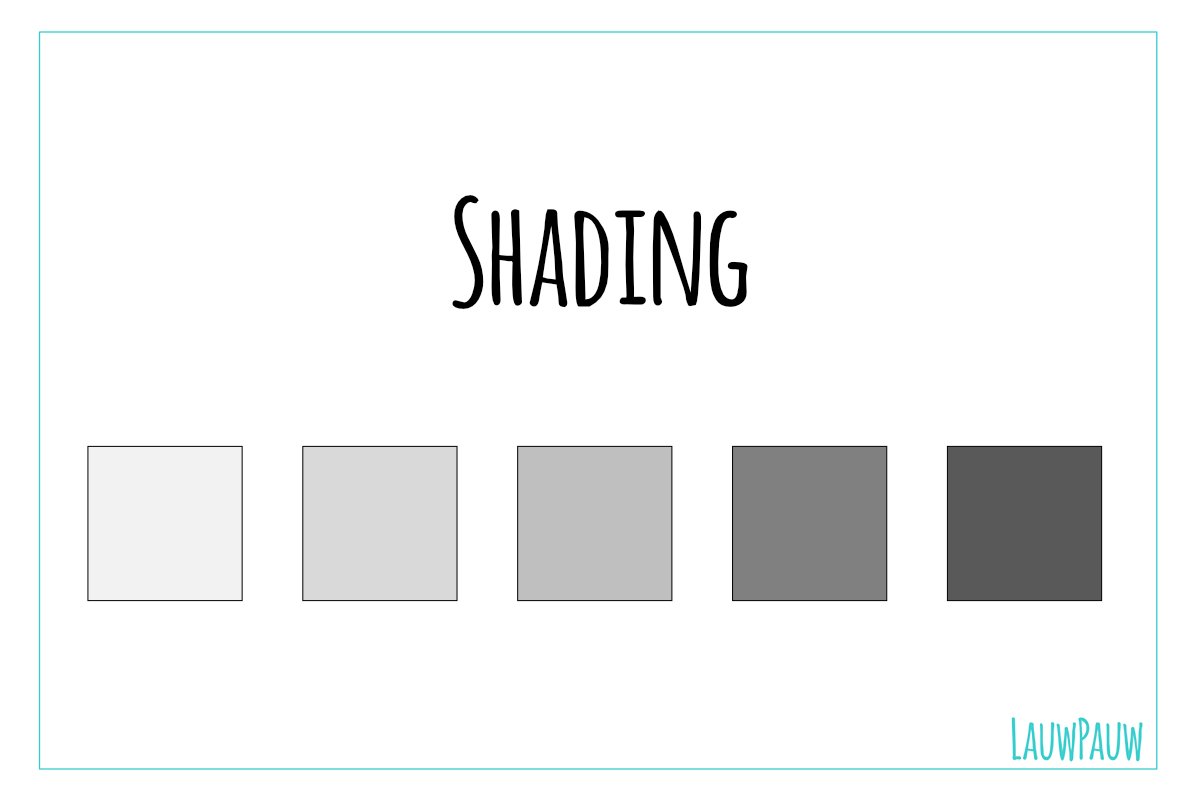

Writers are master painters, and their canvas is your imagination. Just as artists use color to evoke emotion, authors intentionally weave color symbolism into their narratives to add depth, insight, and mood. These hues aren't just descriptive; they draw attention to symbolic objects, convey unspoken information about characters, or subtly highlight crucial themes.

Consider the stark contrast between pastel colors, which might suggest dreaminess, innocence, or nostalgia, and darker colors, which often imply mystery, foreboding, solemnity, or even menace. This intentional deployment of color is a cornerstone of Symbolism & Darker Tones Analysis.

While color meanings can vary culturally, here's a look at common associations, often with a nod to their darker implications:

- Black:

- Common Associations: Death, evil, grief, mourning, mystery, formality, power, sophistication.

- Darker Tones: Despair, emptiness, oppression, menace, villainy. (Think the "black hat" villain trope).

- Blue:

- Common Associations: Serenity, tranquility, calm, stability, loyalty, wisdom.

- Darker Tones: Sadness, melancholy, isolation, coldness, depression (the "blues").

- Brown:

- Common Associations: Stability, comfort, groundedness, earthiness, humility, naturalness.

- Darker Tones: Dullness, predictability, poverty, decay, grime.

- Green:

- Common Associations: Growth, rebirth, nature, peace, renewal, fertility, hope.

- Darker Tones: Jealousy, envy, greed, illness, corruption (e.g., "green with envy," toxic green).

- Orange:

- Common Associations: Energy, enthusiasm, joy, creativity, warmth, autumn.

- Darker Tones: Heat, fire, aggression, warning (often used in safety warnings).

- Pink:

- Common Associations: Love, kindness, femininity, innocence, playfulness, sweetness.

- Darker Tones: Naivety, weakness, superficiality (sometimes ironically used to mask something sinister).

- Purple:

- Common Associations: Royalty, nobility, spirituality, mystery, luxury, magic, wisdom.

- Darker Tones: Arrogance, decadence, mourning (in some cultures), oppression.

- Red:

- Common Associations: Passion, lust, love, romance, energy, courage.

- Darker Tones: Violence, danger, anger, blood, aggression, warning. This is perhaps the most powerful color for conveying intense, often conflicting, emotions.

- White:

- Common Associations: Innocence, peace, cleanliness, purity, virginity, new beginnings (Western cultures).

- Darker Tones: Coldness, emptiness, isolation, sterility, fear, mourning (some East Asian cultures).

- Yellow:

- Common Associations: Creativity, happiness, optimism, intellect, sunshine, warmth.

- Darker Tones: Cowardice ("yellow-bellied"), deceit, sickness, madness, caution (e.g., warning tape).

By paying close attention to these chromatic choices, you can unlock a deeper appreciation for an author's subtle craft in shaping your emotional response and understanding of the narrative.

Literary Masterstrokes: Famous Examples of Symbolism & Darker Tones

Great authors don't just tell stories; they craft experiences, using symbolism to embed layers of meaning that enrich the narrative and often hint at its darker undercurrents. Let's look at some iconic examples where symbolism, particularly color, plays a pivotal role:

F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby: The Green Light

Perhaps one of the most famous literary symbols, the green light at the end of Daisy Buchanan's dock in The Great Gatsby is far more than just a navigational beacon. For Jay Gatsby, it symbolizes his obsessive desire for wealth, his unattainable dream of a lost past with Daisy, and the corrupt illusion of the American Dream itself. The "green" here is tinged with the darker hues of jealousy, greed, and the destructive nature of unattainable desire. It represents a future Gatsby is forever reaching for, a future that, like a mirage, recedes the closer he gets, ultimately leading to tragedy.

Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter: The Scarlet 'A'

Hester Prynne's embroidered scarlet "A" is not merely a mark of shame; it's a potent and evolving symbol. Initially forced upon her by her Puritan community to signify "Adulterer," it represents her sin of lust and infidelity. However, over time, Hester's resilience and quiet dignity transform the symbol in the eyes of many. It begins to signify "Able" or "Angel," reflecting her strength and compassion. Yet, its scarlet hue also subtly suggests the burning passion, frustration, and anger that simmer beneath the surface of her outwardly penitent life, embodying the complex struggle between societal judgment and individual spirit.

The Brothers Grimm's Snow White: The Deceptive Apple

In the classic fairy tale of Snow White, the poisoned apple is a brilliant use of color symbolism to mask malevolent intent. The apple isn't uniformly sinister; it's often described as being half red and half white. The vibrant red side overtly symbolizes temptation, the Queen's evil desire to spill blood, and the apple's alluring (but deadly) nature. The pure white side, however, cleverly symbolizes Snow White's innocence and purity, making the apple appear wholesome and safe. This deceptive contrast makes the apple an even more potent symbol of corrupted beauty and hidden danger, perfectly illustrating how something seemingly innocuous can harbor the darkest intentions.

Even in works that appear lighthearted on the surface, Symbolism & Darker Tones Analysis can reveal significant underlying meanings. Consider how complex narratives like those found in the One Piece Baron Omatsuri guide often employ visual or thematic symbolism to convey character states, foreshadow conflict, or even introduce surprisingly dark philosophical questions, even amidst a vibrant adventure. Authors constantly play with these layers, inviting attentive readers to dig deeper.

Beyond the Obvious: Subverting Symbols and Creating New Meanings

While understanding conventional symbols is foundational, truly skilled writers don't always stick to the script. They often deliberately subvert established meanings, twisting familiar imagery in unexpected ways to challenge reader expectations, create irony, or inject profound "darker tones" into their narratives.

Imagine a story where a white dove, usually a symbol of peace and purity, repeatedly appears just before acts of shocking violence. This subversion forces the reader to confront a disturbing dissonance, questioning the nature of peace or perhaps suggesting that innocence is always a prelude to suffering in this particular world. Such a technique can make a narrative unsettling, memorable, and deeply thought-provoking.

Authors might also create entirely new symbols within the context of their specific story. A recurring, seemingly mundane object – say, a chipped porcelain doll or a broken compass – can, through its consistent appearance alongside particular events or emotional states, accumulate symbolic weight unique to that narrative. Its meaning isn't pre-defined; it's built and reinforced through the story's progression. This requires the reader to be extra attentive to the indicators we discussed earlier: repetition, lingering description, and plot relevance.

This ability to play with, reinvent, and establish symbols is a hallmark of sophisticated storytelling. It invites readers into a collaborative act of meaning-making, transforming passive consumption into active, interpretive engagement.

Common Misconceptions & Pitfalls to Avoid in Symbolism Analysis

As powerful as Symbolism & Darker Tones Analysis can be, it's easy to stumble. Here are some common misconceptions and pitfalls to watch out for:

- Over-analyzing Everything: Remember Freud's snake? Not every single detail in a story is symbolic. Sometimes a tree is just a tree, providing shade. Don't force symbolic meaning onto every object or event, as this can detract from the sheer enjoyment of the narrative and lead to far-fetched interpretations that the text doesn't support. Focus on the indicators (repetition, lingering description, conventional meaning) to guide your analysis.

- Ignoring Context: As we've discussed, cultural context is paramount. Assuming a symbol's meaning is universal can lead to significant misinterpretations. Similarly, ignoring the historical or biographical context of the author or the time period the story was written can blind you to intended nuances or critiques. Always consider the world from which the story emerged.

- Imposing Personal Meaning: While your personal response to a symbol is valid, an academic or critical analysis requires you to ground your interpretations in the text itself. Don't project your own associations onto a symbol if the narrative doesn't offer clues to support that meaning. The goal is to understand what the author intended or what the text suggests, not simply what the symbol means to you personally.

- Looking for "One Right Answer": Literary symbolism is often intentionally ambiguous, designed to invite multiple interpretations. There isn't always a single, definitive meaning for every symbol. Acknowledge this complexity and explore the various possibilities the text opens up, rather than trying to force a singular reading. The richness often lies in the multiplicity of meanings.

- Confusing Symbolism with Metaphor or Simile: While related, it's important to remember the distinction. A metaphor (e.g., "life is a journey") is a direct comparison. A simile (e.g., "life is like a journey") uses "like" or "as." A symbol is a concrete object or event within the narrative that represents an abstract idea. Keep these tools distinct in your analytical toolkit.

By being mindful of these potential missteps, you can ensure your symbolism analysis remains robust, insightful, and anchored in the text itself.

Your Toolkit for Deeper Reading: Becoming a Symbol Detective

Understanding Symbolism & Darker Tones Analysis isn't just an academic exercise; it's a skill that profoundly enriches your engagement with all forms of storytelling. It transforms you from a passive receiver of information into an active participant in the narrative's creation of meaning.

To truly become a symbol detective, cultivate these habits:

- Read Actively: Don't just skim. Pay attention to descriptive passages, recurring images, and elements that seem out of place or receive unusual emphasis. Keep a mental (or actual) note of these details.

- Question Everything: Why is this object here? Why is it described this way? What does this color choice suggest? Don't accept things at face value.

- Research Context: If you're reading a text from an unfamiliar culture or historical period, a little background research can illuminate conventional symbols you might otherwise miss.

- Discuss and Debate: Share your interpretations with others. Hearing different perspectives can challenge your assumptions and reveal layers of meaning you hadn't considered.

- Embrace Ambiguity: Great literature often thrives on complexity. Be comfortable with symbols that hold multiple, sometimes contradictory, meanings. This ambiguity is part of their power.

- Trust Your Gut (Then Verify): If an object or event feels significant, it probably is. Follow that intuition, then use the analytical steps we've covered to ground your interpretation in textual evidence.

By honing your ability to analyze symbolism and its often darker undertones, you gain access to the deeper currents of fiction. You'll not only understand what a story is about, but how it works its magic, how it stirs emotions, challenges beliefs, and leaves a lasting impression. It’s a journey into the heart of human meaning-making, one concrete detail, one abstract idea, one powerful color choice at a time.